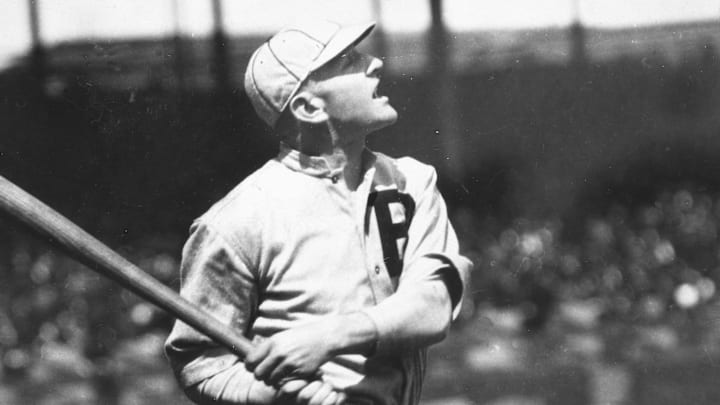

Jim Kaat

The year before Scott Rolen got his call to the Hall, pitcher Jim Kaat was voted in by the Golden Days Era Committee, 39 years after his last MLB appearance. Kaat made five stops during his career, most notably 15 years with the Minnesota Twins, where he won 190 games and amassed over 1,800 strikeouts.

Following his Minnesota tenure, Kaat had a successful stint with the Chicago White Sox. He then spent parts of four years with the Phillies from 1976 through 1979, playing on some very good teams in his last few years as a starting pitcher before transitioning into the relief role that would define the last few years of his career.

All told, Kaat would make 102 appearances (87 starts) for the Phils, putting up a record of 27-30 over 536 2/3 innings pitched. He made one postseason start for the Phillies, taking the loss in a 1976 NLCS contest despite posting a quality start.

He did manage to win a pair of Gold Gloves during his time in Philadelphia, the final two of the impressive 16 that he would amass during his career. At the time, it tied him with Brooks Robinson for the most Gold Gloves in MLB history, but Greg Maddux would pick up 18 such awards during his career to relegate Kaat to second place among pitchers and tied for second overall.

Kaat found himself as a spare part on the 1979 Phillies club, and his contract was purchased by the New York Yankees. He went to the St. Louis Cardinals a few years later, putting an exclamation point on his career as a member of the 1982 World Series champions.