In the midst of MLB’s ninth work stoppage in the history of the game, it’s fitting to honor Curt Flood on the anniversary of the union meeting at which he made his case.

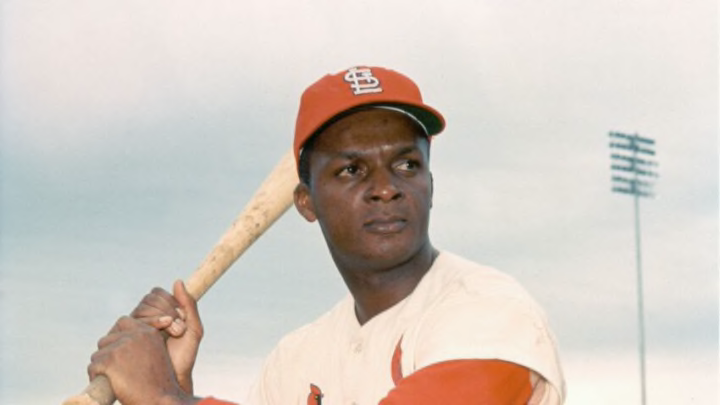

Between 1956-1969, Flood played for Cincinnati and then St. Louis. Twice, the outfielder led MLB in at-bats, and once in hits. Between 1963-69, he played in three All-Star Games, helped the Cardinals win three pennants and two World Series, and won a Gold Glove every single season. In 1968, Sports Illustrated named him “Baseball’s Best Center Fielder.”

Flood’s relationship with his team began to sour ahead of the 1969 season. He wanted a significant raise, and the Cardinals weren’t willing to pay up. Instead, they began a smear campaign against him and removed him as co-captain.

Then, in October, the Cards traded Flood to the Phillies. Flood knew what Dick Allen – who was snubbed by the Hall of Fame earlier this month – had endured at the hands of Phillies fans. And Flood was actually being traded, along with other players, in exchange for Allen.

"“Philadelphia. The nation’s northernmost southern city. Scene of Richie Allen’s ordeals. Home of a ballclub rivaled only by the Pirates as the least cheerful organization in the league… I did not want to succeed Richie Allen in the affections of that organization, its press and its catcalling, missile-hurling audience.”Curt Flood"

While the Phillies did offer Flood significantly more than the raise the Cardinals had denied him the year before, Flood did not want to play for them. He refused to report to Philadelphia.

On December 13, 1969, MLB star Curt Flood met with the MLBPA about suing the league for free agency, because he did not want to be traded to the Phillies

Instead, on December 13, he went to the MLBPA’s executive committee meeting in Puerto Rico to discuss suing the league for free agency and abolishing the reserve clause, which he felt was tantamount to indentured servitude. Then-head of the players’ union Marvin Miller warned Flood what he was up against:

"“I told him that given the courts’ history of bias towards the owners and their monopoly, he didn’t have a chance in hell of winning. More important than that, I told him even if he won, he’d never get anything out of it—he’d never get a job in baseball again.”"

But then Flood asked Miller if his fight would benefit other players, and the union leader replied that it would help players of his age “and those to come.” The centerfielder replied, “That’s good enough for me.”

Flood received a 25-0 unanimous vote of support from the union.

On Christmas Eve 1969, Flood wrote to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn asking to become MLB’s first true free agent:

"“December 24, 1969After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.”"

Unsurprisingly, Kuhn did not appreciate a player asking to demolish the status quo that kept owners rich and controlled players; he denied Flood’s request.

Flood could have accepted what was then a lucrative contract, but he never wavered. His bravery would cost him everything.

In January 1970, Flood filed a lawsuit against Kuhn and the league, which would eventually be argued before the Supreme Court in 1972. MLB legends including Hank Greenberg and Jackie Robinson testified on Flood’s behalf, as did former owner Bill Veeck. However, many then-current and former stars were opposed to Flood’s fight, including Joe Garagiola, who actually testified against flood in one of the trials. No active players stood by Flood at the time; he was all alone in his fight for everyone’s betterment.

Meanwhile, Flood sat out the 1970 season but returned in 1971 to play 13 games for the Washington Senators, who had effectively offered Flood a deal that included a form of free agency if he did not want to return after the 1971 season. Ted Williams, who had been opposed to Flood’s lawsuit, was his manager.

Despite Williams’ strong show of support for the embattled former star, Flood left the team in late April and never played again.

"“I tried. A year and one-half is too much. Very serious personal problems mounting. Thanks for your confidence and understanding. Flood.”Curt Flood’s telegram to Senators owner Robert Short"

In 1972, SCOTUS voted 5-3 in favor of Major League Baseball. Judge Lewis Powell, who supported Flood but was also an Anheuser-Busch stockholder (Augie Busch owned the Cardinals), withdrew from the case.

However, despite the loss, Flood had knocked over the first domino. While the courts had voted in favor of the league, their decision also subtly criticized the antitrust exemption, which was all Miller needed to take the next step. The Basic Agreement of 1970 included independent arbitration, for players to negotiate certain grievances.

Finally, in 1976, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, who had played without contracts the year before, became what Flood had asked to be: the first free agents. Just like that, the system had collapsed, more a house of cards than the fortress it appeared to be.

By then, Flood was destitute and battling alcoholism. It would take years for him to find his way, and by the time he did, he was diagnosed with cancer. He died in Los Angeles on January 20, 1997, and none of the players of his era attended his funeral. Even in death, baseball was and has been cruel to one of its bravest figures.

Why is MLB in lockout now?

Currently, MLB is in lockout because owners once again want to avoid treating their players fairly. Free agency remains one of the key issues; players cannot become free agents until they reach six years of service time.

In his day, Flood stood alone. During the current ongoing lockout, we’re seeing players speak out and use social media to take a stand. Phillies star Rhys Hoskins is one of many making his feelings on the lockout abundantly clear, but he and his fellow ballplayers are only able to do so in large part because of Flood.

Baseball has come so far since Flood fought, but on this anniversary and every day, we are reminded that there is so much work still to be done.